50 Years, 50 Legacies: Moose River Indian Village

50 Legacies: Moose River Indian Village

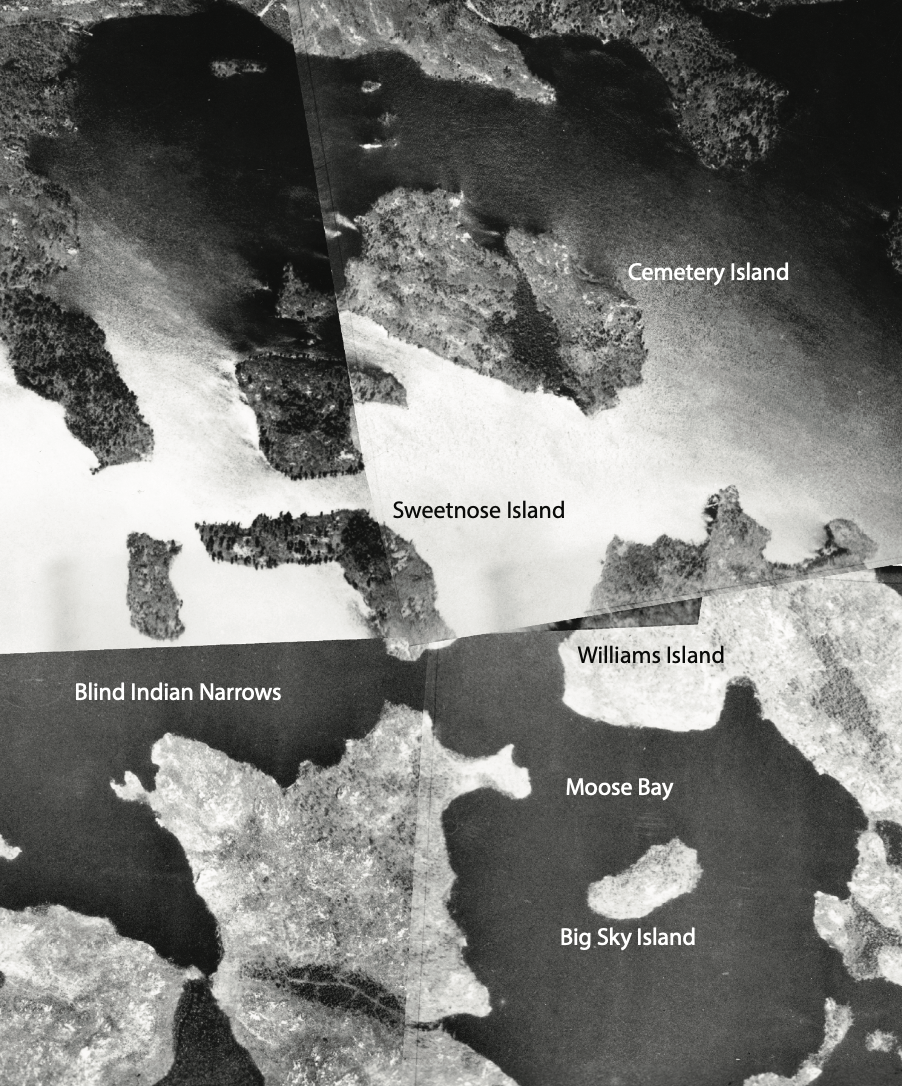

The ‘Moose River Indian village’ on Namakan Lake was a dispersed settlement of Bois Forte Ojibwe families, 1927. (Credit: VNP)

Indigenous people have lived within and outside the bounds of Voyageurs National Park for tens of thousands of years. The Ojibwe were the most recent group of stewards of the lands of Voyageurs National Park; prior to this the Cree, Dakota, and Assiniboine also historically stewarded the land. We recognize that Indigenous peoples have stewarded the land of Voyageurs National Park for generations and remain deeply connected to its landscape and stories.

The Bois Forte Ojibwe lived within the park from the 1760s-1930s. An 1866 treaty with the U.S. government required the Bois Forte Ojibwe to give up their land and move to the Nett Lake reservation. Despite this, many Ojibwe families continued to occupy their traditional lands. Some of these families acquired land ownership through the 1863 Homestead Act, purchased it, or acquired it through the 1887 General Allotment Act, an act that ended tribal ownership of land and replaced it with individual ownership.

The Moose River Indian Village encompassed a five square mile area on Namakan Lake from the 1770s to 1941. The Ojibwe here lived within their traditional waginogans, dome-shaped lodges covered with birchbark. The dome-shape of these dwellings were meant to honor the muskrat by imitating the shape of their homes. These lodges could easily be packed and moved between settlements. The Moose River Village was connected to other settlements by the navigable canoe “water highways” of the park as well as a network of trails. These trails extended from Vermillion Lake to Gold Portage, from Nett Lake to Lake Kabetogama, and from Ash River to Moose River.

While primarily living year-round on Namakan Lake, The Ojibwe also moved between settlements by birch bark canoe to follow seasonal harvests. During Ziigwan, or spring, they would live in the sugar bush, an area abundant with maple trees, where they would collect and boil down sap to maple sugar. Niibin, or summer, families would live within summer villages where they spent time harvesting berries and plants. During Dagwaagin, or fall, they would move to rice lakes and work together to harvest and process wild rice for the winter. Biboon, or winter, is when families would move to their winter camps within the forest. During the 1920s, the Ojibwe became more involved in the European-American economy where they traded berries and fish commercially. The last Bois Forte Ojibwe to live within the village, and in the bounds of the greater National Park, was Joe Whiteman. He remained within the village until 1940 in a log cabin with his pony named Lady and his dog.

Ojibwe dwelling at Crane Lake, ca1930. (Minnesota Historical Society, #E97.31p83, Neg. #53158, Acc. #YR1962.3918)

Hauling blueberries across Namakan Lake. The Bois Forte Ojibwe traveled in birch bark canoes, and moved seasonally to find food. (VNP Bowser collection, Catalog #1681)

The Bois Forte Ojibwe still retain a strong connection to their traditional lands within the park. If you would like to learn more about the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa today, please visit their official website or the Bois Forte Heritage Center & Cultural Museum, located approximately one hour southeast of Voyageurs National Park.

Check out the full list of our 50 legacies!

This year, we’re celebrating 50 years of Voyageurs National Park by sharing 50 inspiring stories of the people who shaped its legacy. Years, 50 Legacies is a yearlong storytelling series highlighting individuals whose lives are woven into the fabric of the park – whether through conservation work, cultural traditions, recreation, research, or personal connection.

Raise a canteen and celebrate this historic milestone with us at our 50th anniversary website. Don't forget to subscribe to our newsletter for more inspiring stories and updates!