The Myth of the Lone Wolf: Navigating the Wilderness of Dispersal

Written by Maeve Rogers, Wolf Predation & Research Technician

Have you ever been called a 'lone wolf'? Some wear it as a badge of honor, while others may see it as a label for those who prefer solitude. However, the term "lone wolf" often carries negative connotations in human society. It's true that in human societies, we often use the term ‘lone wolf’ to describe individuals who are perceived as unsocial, eccentric, or possibly even threatening. None of these associations are inherently positive and may cast a shadow of negativity on the brief solitary nature of wolves.

But what if being a lone wolf meant more than just a personality trait? In the wild, it can be the difference between life and death.

The Natural Cycle of Dispersal in Wolf Packs

Wolves, renowned for their highly social nature, thrive in complex pack structures typically led by a breeding pair and their offspring. However, there comes a time when everyone must venture out on their own, and wolves are no exception to this rule of nature. This period known as “dispersal” marks a pivotal and perilous chapter in a wild wolf's life. Dispersal is defined as the permanent movement of an individual wolf from one pack’s territory to a new territory - typically to find mates and form new packs! Dispersing individuals are often leaving their natal habitat, which is the place in which they were born. Other times, older adult wolves may disperse if their territory was taken over by a new pack or a mate died. When animals disperse, they're usually on the lookout for a mate or better resources like food and space. The primary motivation behind these departures is believed to be intense competition for food within the pack. In other words, wolves often choose to leave their packs and become solitary hunters because they seek better opportunities elsewhere. Interestingly enough, not many wolves survive this challenging life stage and mortality rates are known to be high but still relatively understudied in most areas.

Maeve Rogers, Wolf Predation & Research Technician, collecting data from wolf P3S. Credit: Voyageurs Wolf Project

Biologists have been studying wolf dispersal movements for a while, often using devices like GPS (Global Positioning System) or VHF (Very High Frequency) also known as ‘pulse’ collars. Through these methods, some fascinating things have been discovered. There have been a few observations of wolves from the same family or group traveling crazy distances—over 100-300 kilometers—and ending up settling near each other again. It's like they have a secret rendezvous point!

Even more intriguing, biologists think there might be a hidden pattern behind these journeys. It could be something in their genes or maybe they learn from each other about where to go. Imagine if your family members always ended up moving to the same neighborhood, even if you didn't plan it! Thanks to modern GPS technology, scientists today can track these wolf travels better than ever before. This technology lets them peek into the intricate strategies and patterns behind long-distance wolf dispersals. Who knows what other secrets of the wild these wildlife tracking technologies will unveil next?

Case Studies: Dispersal in Wolf Packs

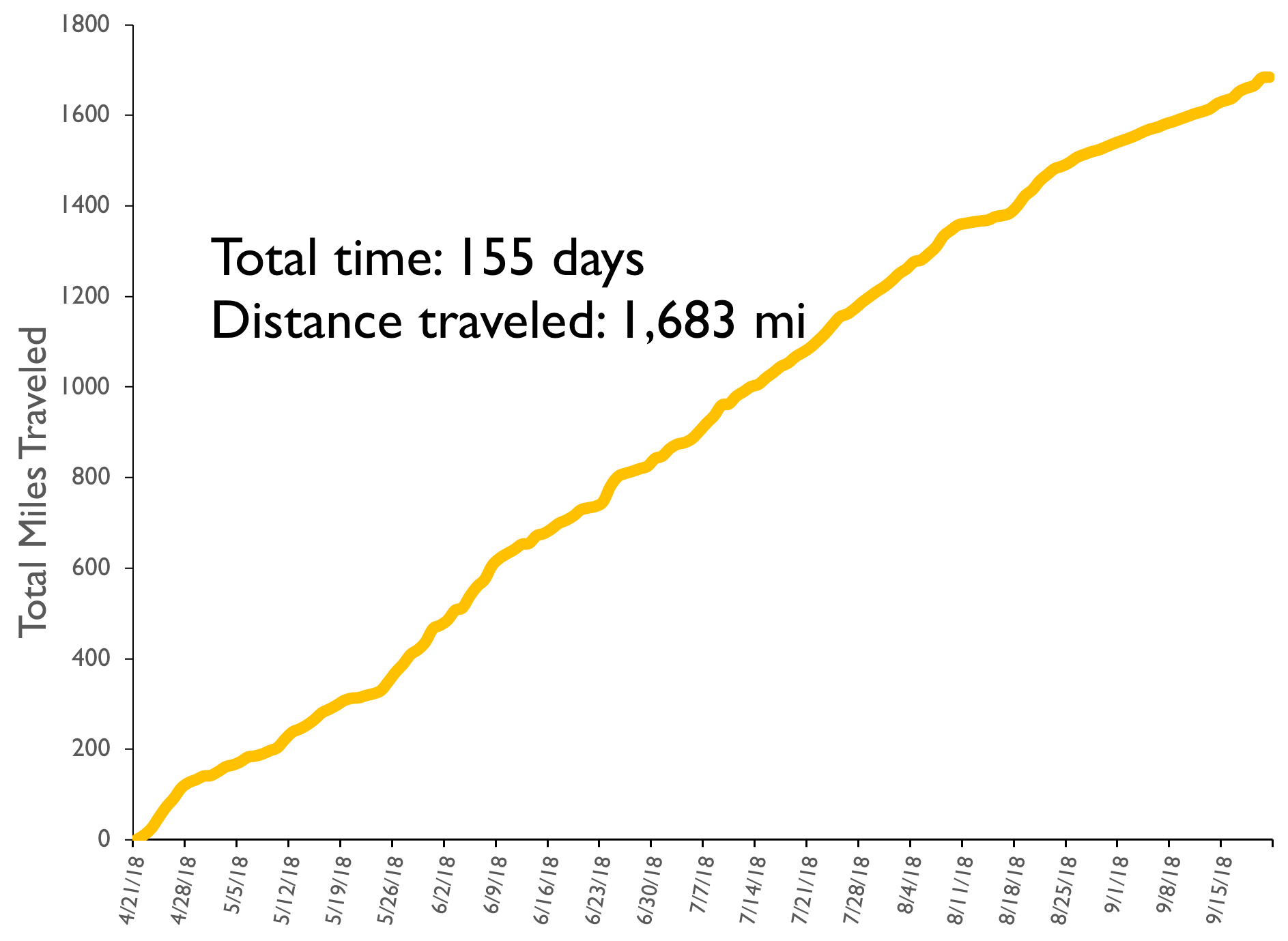

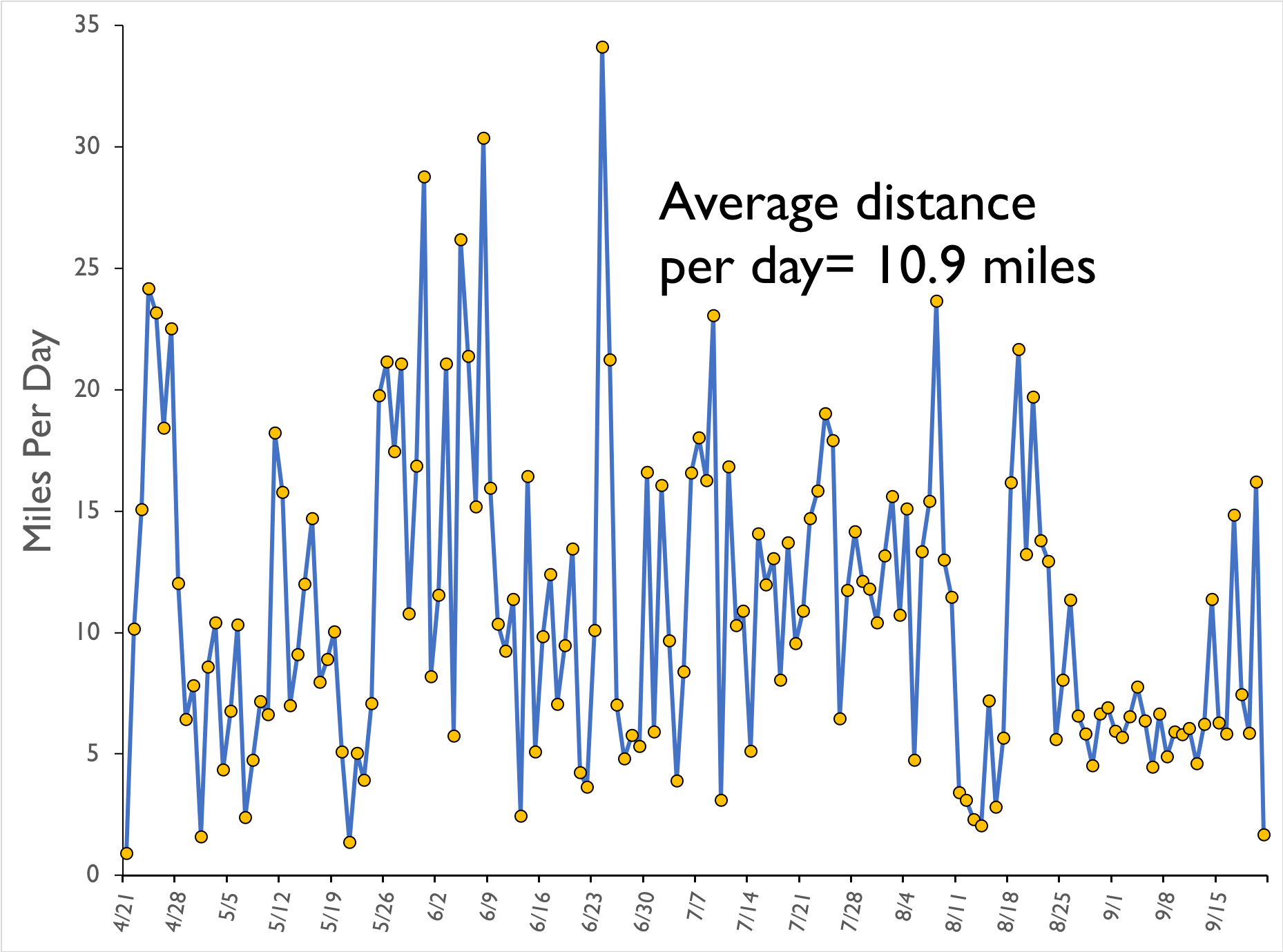

So how far do wolves travel in a typical day or during dispersal? Well, in short, it can depend on many different factors. For example, one wolf collared and studied by the Voyageurs Wolf Project gave researchers a great example of the long-distance journey wolf dispersal can become. Wolf V057, originally dispersed nearby Voyageurs National Park northwards to Red Lake, Ontario in 2018. Wolf V057’s GPS tracking collar showed biologists that he covered some significant ground in a fairly short amount of time. As shown in the graphs below, V057's journey was extensive. If we were to assume a consistent average distance traveled per day for this wolf, which would be approximately 10.9 miles, V057 would have traversed an impressive 3,978 miles within a single calendar year! Covering an average of 10-11 miles daily is suspected not to be uncommon for many individual wolves.

Graphs of wolf V052’s travel data. Credit: Voyageurs Wolf Project

On the other hand, the Voyageurs Wolf Project documented a wolf dispersing just a few short miles to stake out a new territory essentially bordering her natal habitat. The project initially collared V052 as a 1-2 year old female in the Sheep Ranch Pack back in 2016. Unfortunately, her collar failed that fall and the last sighting of her dates back to late October 2016. After 5 years of absence, Wolf V052 reemerged in the spring of 2021 thanks to a stroke of good luck and some fortuitous trail camera captures! This discovery is particularly remarkable considering that five years is considered to be a long lifespan for a wild wolf, as most wolves don't exceed five years let alone much longer than one to three years of age.

It quickly became apparent that wolf V052 was part of a newly identified pack, which was named the Bluebird Lake Pack. This pack occupied the region east of the Huron Pack and south of the Wiyapka Lake Pack, and V052 served as the breeding female. Therefore, wolf V052 dispersed from the Sheep Ranch Pack to later become the breeding female of the Bluebird Lake Pack sometime between late 2016 and 2021. Little did researchers know that their paths would cross again 6 years later when the project was able to recapture wolf V052 in the summer of 2022. It was necessary to replace V052's green ear-tags as it seemed like the pups or other wolves chewed off the ends. Nevertheless, the tags fulfilled their purpose, enabling researchers to identify her six years later. Her new ear-tags were purple, and she then became known as wolf P3S.

Wolf V052 (P3S). Credit: Voyageurs Wolf Project

Later that winter, P3S (V052) and her mate P0C were killed by a rival pack that dispersed into their territory. Although very unfortunate to lose two important breeding animals, it gave the project an opportunity to collect data on pack turnover and interactions between dispersing wolves and a highly established pack.

Biologists estimate that approximately ~15-20% of any wolf populations consist of lone wolves, which constitutes a significant portion! These lone wolves are typically young, aged between 1 to 3 years old, who have departed from their birth pack in pursuit of establishing their territory and finding a mate. Nevertheless, the age range can vary as older and more experienced wolves might also find themselves in search of new territory and a mate. Events like this can occur often in areas where “pack turnover” is high. Pack turnover is when an existing pack in a territory is replaced by a new pack that takes over that territory often by outcompeting or eliminating the existing wolves. In northern Minnesota near Voyageurs National Park, during pack turnover or the formation of a new pack, it's common for only a breeding pair (comprising just 2 wolves) to assume control of or inhabit the territory.

Wolf V052 (P3S). Credit: Voyageurs Wolf Project

Many wolves that eventually reproduce or live a long life, typically around 8-10 years, will have spent a period of time in solitude as lone wolves. In fact, it's quite rare for wolves to assume the role of breeding or dominant wolves without first venturing out on their own. In essence, leaving the pack is kind of like a prerequisite for wolves seeking mates and producing offspring. The dispersal of wolves from their packs and their subsequent pairing with mates from other territories contribute positively to wolf populations. This behavior helps prevent inbreeding and promotes genetic diversity. Lone wolves have the opportunity to find mates unrelated to them, thereby enriching the gene pool. Without wolves leaving their packs, the risk of perpetual inbreeding would be a real problem. Wolf packs primarily consist of family members, which increases the likelihood of continual mating among closely related individuals. This scenario would pose significant threats to the overall health and sustainability of wolf populations.

Embracing the Lone Wolf Mentality

Graphic by Maeve Rogers

Being a lone wolf does have its perils. Indeed, lone wolves typically are at a higher risk of death because they are wandering through unknown terrain where they are often trespassing on another pack’s territory or traveling near human infrastructure where they are at a higher risk of getting killed. But all-in-all, this risky life-stage is one that most wolves will face if they live long enough, and it is through this process that wolves find mates, new packs form, and wolf populations persist.

In summary, though, there is nothing sad or concerning about being a lone wolf and choosing to roam in solitude. It is a natural part of their behavior and crucial for maintaining a healthy balance within wolf populations. In nature, a wolf venturing alone is natural and beneficial for wolf populations. It's not an act of isolation or rejection. Rather, it is a display of independence and adaptability crucial for genetic diversity and territory expansion. For wolf populations, the presence of lone wolves is essential for genetic diversity and the dispersal of individuals across different habitats. Solo wolves play a vital role in expanding the range of wolf territories and preventing inbreeding within packs.